HOPKINSVILLE, KY (CHRISTIAN COUNTY NOW) – As Black History Month is observed across the nation, the influence of prominent figures is proudly displayed throughout the City of Hopkinsville. Murals, historical markers, exhibits, and structures all carry important elements of Black history.

2026 marks 100 years of the acknowledgment of Black History Month, with Hopkinsville Mayor J.R. Knight reading a proclamation at the beginning of February with Human Rights Commission. It read in part, “We should take the time to celebrate the vast contributions of Black Americans, honor the legacies and achievements of generations past, reckon with centuries of injustice, and confront those injustices that still fester day.”

Here are a few notable snapshots of Black History that are visible in Hopkinsville all year including Vine Street Cemetery, Peter Postell, Elder Watson Diggs, and Attucks High School.

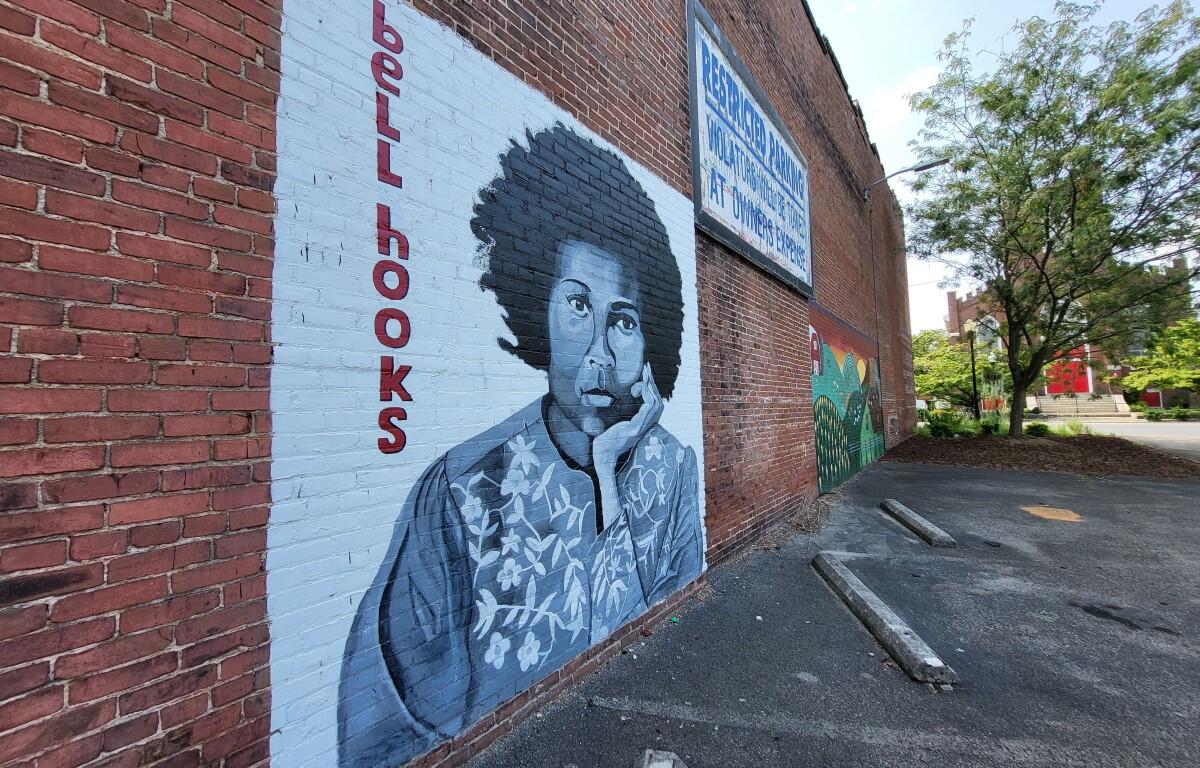

bell hooks

Born Gloria Watkins and utilizing the lowercased penname bell hooks, she is a nationally recognized author and poet and Hopkinsville native who published over 40 books in her lifetime mostly focused on themes of feminism, race, and class. Standout titles including “All About Love” and “Bone Black”.

Born on Sept. 25, 1952, hooks graduated from Hopkinsville High School and went on to be a professor at multiple colleges. She won the National Book Award for Fiction and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, according to information from the National Museum of African American History and Culture. In 2010, Berea College in Kentucky opened the bell hooks Institute, which serves as a center for her poems, novels, and personal items.

bell hooks’ face is proudly displayed on a downtown Hopkinsville mural, there is book club dedicated to her works, a local street is named in her honor outside of the old Carnegie Library, and a wing is dedicated to her in the Pennyroyal Area Museum.

| FIND US ON SOCIAL MEDIA: Follow Christian County Now on Facebook

Ted Poston

A historical marker for Poston was erected in 2017 by the Hopkinsville Farmers Market. Known as the “Dean of Black Journalists,” Poston was born in Hopkinsville on July 4, 1906, and was a graduate of Attucks High School. The historical marker says that after a string of various reporter positions, he began freelance writing for the New York Post in 1936 and was soon hired full time.

His successful career earned him a Pulitzer Prize nomination in 1949 for a series of articles titled “Horror in the Sunny South,” according to the Kentucky Historical Society. He died in 1974 and is buried in Cave Springs Cemetery in Hopkinsville.

Poston wrote short stories about his life called “The Dark Side of Hopkinsville,” which was published after he died in 1991. He was inducted into the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame in 2000.

Attucks High School

Built in 1916, Attucks High School in Hopkinsville served as the first public school for black students in the area. In 1988, the school closed and ceased operations leaving the building to deteriorate. It was named after Black Revolutionary War hero Crispus Attucks who became a symbol of the abolitionist movement.

To honor the legacy of the school, local nonprofit Men 2 Be has been actively working to restore the building and create a community center that includes apartments, a functional gym, emergency shelter, food pantry, and spaces for community programming.

The nonprofit was created to empower Black youth and allow them to reach their full academic, social, and personal potential through brotherhood. Boys are provided mentors and taught life skills while engaging with the local community.

| STAY UPDATED ON LOCAL NEWS: Sign up for the midday Christian County Now newsletter.

Peter Postell

Considered one of the wealthiest black men in the south, Postell was born into slavery in 1841 in North Carolina, and was later brought to Kentucky, according to a historical marker in Hopkinsville. He later escaped his enslaver and joined the 16th U.S. Colored Infantry during the Civil War, returning to Hopkinsville to establish a successful grocery business.

His business ventures expanded into real estate, investments and philanthropy in the community. He died in 1901 and is buried at Cave Springs Cemetery in Hopkinsville. A historic marker honoring his impact is located on the former site of his store on Sixth Street.

Union Benevolent Cemetery

The cemetery was established in 1866 by the Union Benevolent Society, an organization of newly freed African Americans just after the conclusion of the Civil War. The group was one of several black benevolent societies locally and nationally. It served the purpose of financially caring for widows and orphans and for providing a burial place for its members, according to the Museums of Hopkinsville-Christian County.

Commonly referred to as Vine Street Cemetery, this site is the final resting place of hundreds of local residents including dozens of African American veterans of the Civil War.

The cemetery ceased to be used as an active burial ground in the mid-20th century and is now owned and maintained by the City of Hopkinsville. During the summer, volunteers with the museum set dates to properly and respectfully clean tombstones.

Elder Watson Diggs

A mural of Diggs is displayed at Founders Square in downtown Hopkinsville. Born in Hopkinsville in 1883, he was a co-founder of the nation’s second oldest historically black intercollegiate fraternity. Alongside nine other students in 1911, he played a key role in shaping traditions and insignia for Kappa Alpha Psi.

Diggs was a WWI veteran before becoming a school principal in Indianapolis. The Kentucky Commission on Human Rights says that in 1916, Diggs became the first African American graduate of the Indiana University School of Education. He envisioned that the creation of the fraternity would help give black men support and sanctuary.

Dr. Bankie Oliver Moore and Mamie More

Dr. Bankie Oliver Moore and his wife Mamie dedicated their lives to helping the people of Hopkinsville and Christian County. Dr. Moore’s 40-year career as a physician and surgeon improved the health care available to African Americans in the community, according to the Museums of Hopkinsville-Christian County Their home at 1030 East Fourth Street was constructed between 1917 and 1920, which has recently been added to the National Register of Historic Places. The owner of the structure has invested time to restore the home over the past few years.

Dr. Moore was a Christian County native who returned to Hopkinsville after graduating from Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. He opened a private practice in 1914 to treat the local Black community. At the time, he was among the earliest African American doctors to practice in Hopkinsville and was notably the first Black native Christian Countian to do so.

| DOWNLOAD THE APP: Sign up for our free Christian County Now app